One of the most persistent (and often valid) criticisms of Africa’s venture capital ecosystem is that investors rarely publish case studies, reports, or essays outlining their thesis or track record. The result is an ecosystem where data beyond funding amounts is scarce, making it nearly impossible to track investor performance, portfolio impact, or sector-level learnings over time.

But, EchoVC, a venture capital firm which counts Shuttlers and Cellulant among its portfolio companies, went against the norm. In September, it released a report that details the performance of its $2.5 million climate tech fund, which includes the fact that most climate tech startups do not need to raise equity capital, as a combination of equity, grants, and assets represent their best chance of achieving scale.

Launched in 2023, the EchoVC Eco Pilot Fund was raised in partnership with Shell Foundation and UKAid as an experimental fund designed to back African founders building climate and climate-adjacent solutions, especially those serving smallholder farmers, transporters, and microentrepreneurs (MEs).

The fund had two main objectives: write the first institutional cheques into founder-led African climate startups and test flexible financing and support structures for under-represented founders and underfunded sectors. The fund was intentionally designed as an experiment, each investment becoming “a small, high-learning, thoughtful experiment” with limited downside and significant upside.

Two years later, it has backed 15 startups across sectors like energy storage, clean cooking, renewables, smart mini-grids, waste management, cooling, mobility, and the circular economy.

For this week’s Ask an Investor, I spoke with Eghosa Omoigui, the managing partner of EchoVC, to understand why his firm prefers microfunds, his thoughts on how much funds should be raised, why equity does not work for climate tech startups, the missing middle in early-stage startup financing, and why development finance should be rethought for Africa.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why does EchoVC mostly use microfunds? It’s something I have been curious about since I noticed that’s your fund’s strategy.

We just think that they’re just better for the ecosystem. They meet the market where it is. When you raise a large fund, you want to write a $10 million cheque, but the challenge is that once you raise a fund that size, you start making very different deployment decisions. Eventually—where the market really needs a lot of help, which is under a million dollars—it just doesn’t make sense for you to write that size of cheque. We realised that the small-footprint vehicles are just better suited for the market.

When there’s a small footprint, there are a few other things that come alongside that. One is that you are writing smaller cheques. Two is that you’re actually giving people permission to fail. With the bigger cheques, then you get all kinds of incentives coming into the equation—behaviours trying to preserve the look—whereas with smaller cheques, you fail, you fail. The final thing: in terms of how you drive liquidity—small cheques, low valuations—which means you can get lower-priced outcomes that are still really good.

If you are writing a $5 million cheque out of a $100 million fund at, let’s say, a $25 million post-money valuation, you own 20% of the business. If the company exits at $100 million, your return is 4X—$20 million—which is really good. The problem is you have to return the fund, and when you look at traditional portfolio construction, only a handful of the companies in the portfolio will be able to do that. You’re still struggling to figure out how you’re going to return the fund. If you get some of these international investors to come in who are playing a different game, then expectations go from $100 million to a billion. That means you’re going to really need to work very hard because you’re going to get diluted. Over the years, we’ve realised that the smaller funds are just better suited for this market.

What you’re saying makes sense, especially for early stage… the market is still constrained and we’re not getting exits. Even secondaries are rare.

If a company is worth a hundred million (dollars) and you own 10% and need to exit your entire position, that means the incoming investor has to give you 10 million—you alone. How many of those side secondaries are happening? They’re just not.

In the essay, you criticised LP-fit over market-fit fund sizing. In your opinion, what is the right fund size for seed, and what cheque size/ownership do you target?

Seed funds should really not be more than $30 million. I think Series A funds should be no more than $50—75 million tops. That’s pretty much it, and you’re trying to optimise for 10, 15, 20% ownership.

You also argued that equity doesn’t always work for capital-intensive or hardware startups and that debt should be deployed more often. How should the split look—debt vs. equity?

I don’t know if there is a plain heuristic about the ratios. Everything is very context-dependent and focused on the specific company. Debt is very focused on management maturity and business model maturity. There are different types of debt. We have companies in the portfolio that don’t need long-term loans; they need high-velocity revolving working-capital lines. There’s a mismatch between when they deliver the product, when they can invoice, and when they get paid.

Example: deliver products every day in October. You can’t invoice until November 1 for all of October. Invoices are net 30—so paid November 30—but in Nigeria, net 30 is more like net 60 or 90. Assume net 60: for work in October, invoiced November, you get paid January 31. By the time that first month gets paid, you’ve been delivering October, November, December, and January. Who’s going to pay for that? So it’s designing these “jet lag” products depending on the business model.

We’ve seen small companies give up a lot to factoring companies—“We’re owed this much by this big company; just give me half and I’m happy”—just to get paid on time. That’s predatory. So we can design ways to finish this, help these companies, and help them grow.

The debt vehicle is context-dependent. Some companies need debt because they acquire inputs, create a product, then sell—very different. Having vehicles that are extremely nimble and flexible is critical. We’re confident that once we deploy this for a couple of years, you’ll see a lot more interesting, successful businesses. It’s not just capital that’s the gating item; it’s the type of capital.

If a founder could secure only one non-equity funding type—inventory financing, receivables purchase, FX hedge line, etc.—which should it be?

Great theoretical question, but I can’t answer it. Companies have different product lines and needs. Some buy inputs and can get supplier financing (90-day terms). Depending on the product, you can attract revenue-based financing or factoring (e.g., 20% discount on receivables). Others need hard debt to build a plant. In practice, there isn’t a fixed answer.

You talk about a “missing middle” in your report. If a founder is stuck there—raised too little and it’s taking too long—what can they do?

Hard to offer generic advice; it’s an introspective analysis—founder, team, balance sheet, product, market, fit. More capital gives permission to fail, which is important. Culturally, failure has a high coefficient of drag for us, with mental burden. For a founder stuck there, the grant ecosystem might be the lifeline. It’s hard to navigate, but VC may not be appropriate at that point. If you still believe in an invisible market no one can see, you may need additional proof points from the grant market.

You identified four gaps: pipeline, funding, gender, and the market paradox. What do you mean by “market paradox”?

The example is about founders who can build companies that move the needle. We’re not the only ones who will discover them; the world will. The more friction you put into the system, the more likely an elite founder says, “I’m not doing this rubbish again,” and leaves. When you see an elite founder, back them—give them permission to test, experiment, and fail if necessary. If the system rejects them, someone else will accept them—you lose the opportunity to build a material business, create jobs, create value.

These founders were local, but the world will discover they’re gifted and welcome them. That needs to change—but it isn’t really changing. We see more money going to founders who didn’t attend schools locally. Research showed 92% of climate money in Africa going to non-African founders. We sought to solve that with this pilot fund. People say, “We can’t find them.” Same as with women founders—“we can’t find them.” So we put a collage of pictures: “You say you can’t find them—okay, here are 15. They’ve been found.” It’s about the lenses used in evaluating opportunities. Many invest by pattern matching. Part of why it was important to put that collage was to break your pattern—if you believe the only way to make money in climate investing is by investing in expat founders.

How can VCs plug these gaps?

It’s not an activity; it’s interest. I was talking to everybody in the ecosystem. One thing about specific sector vehicles is you get investors interested in that segment—and companies with similar trajectories. In fintech/remittances, someone goes from $1m a month to $10m, to $60m, momentum looks great—even if net margin is 1%. By year five, they might be at $1b a month and $10m revenue, but margins are skinny.

Climate companies don’t grow with that steep curve, but in year 10, a climate company could be doing $100m revenue with 50% gross margin and 35% net—$35m free cash flow yearly. As an investor, you don’t need a formal exit—no M&A, no IPO—you’re getting a dividend. There are different paths and runways to liquidity; some shorter, some longer, some more persistent.

Example: you put $5m into a climate company and own 10%. It’s a 15-year fund. Between years 10 and 15, at $35m annual free cash flow, your 10% yields $3.5m/year → $17.5m over 5 years (3x in cash), without selling any equity. Your equity becomes an annuity. Next five years, more returns—maybe ~7x over 20 years. Long-dated, but these businesses are long-delayed types. We’re still early in learning this—like the zero-interest-rate-phenomenon era when valuations went ballistic, then ended quickly, then AI hype.

Climate remains interesting: food systems, waste, sustainable transportation—the opportunities are humongous. New energy/solar panels example was just a small illustration; the market size is huge.

Something that stuck out to me is the intentionality behind finding female founders. I went through the companies that you backed; a lot of them are run by women. How were you able to do that?

Quite a bunch of them are solo founders, too. Well, we ran an open-door policy. A few other things we’ve done mechanically. We tend to have women founders—when the pitch is not run through slides, unless they’re very comfortable with that—but it’s their flexibility, because we’ve found historically that when they don’t have slides, they tend to talk about their businesses differently, in fact, in a more helpful way.

But I also think it’s a vibe thing, right? Do they feel that we truly are listening to them? Do they feel that we’re authentically going to evaluate the investment? Do they feel that we’re going to respect them? Do they feel that we’re not going to ask them stupid questions like, “Are you going to get pregnant?”—which, by the way, a lot of investors apparently do that. It’s a vibe thing: you come in and you know that you’re just going to be treated on a very simple axis—do you fit a founder archetype or not?

In the report, you say you backed 15 companies with “low cost of failure” and “uncapped upside.” How do you find these companies, and how do you define those terms?

A lot of founders—founders sent to us. Then we have companies that just come in through our website—we’ll look at everything, and we have quite a few companies where later-stage investors send them to us—“These guys are interesting but too early for us; go to EchoVC. There are a lot of different ways.

How do you define “low cost of failure”?

In this pilot fund, it was an explicit design, it’s $100–200k. And if we miss, it’s fine. We would have learned; the founders and the teams will have learned. We have one company right now that is on track to return the whole fund.

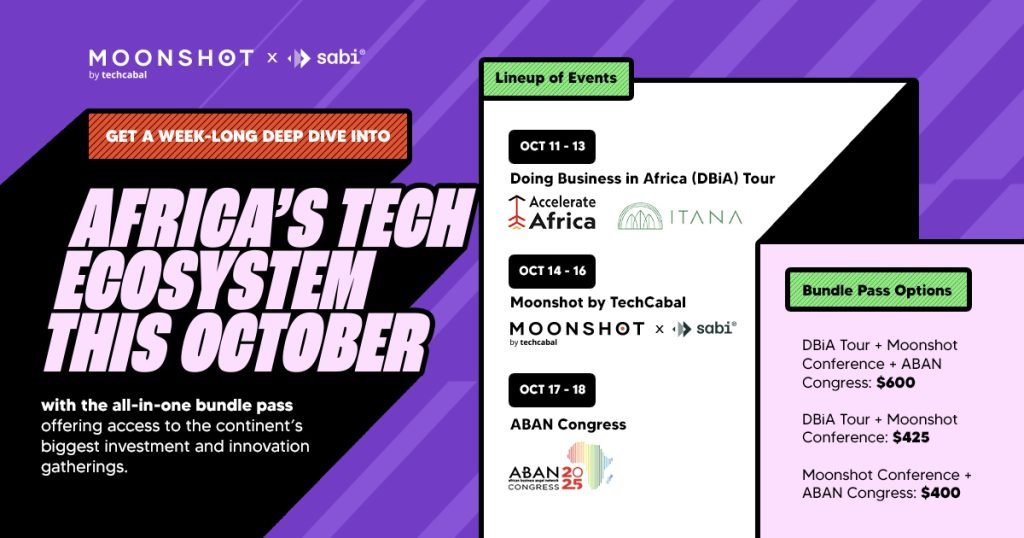

Mark your calendars! Moonshot by TechCabal is back in Lagos on October 15–16! Meet and learn from Africa’s top founders, creatives & tech leaders for 2 days of keynotes, mixers & future-forward ideas. Get your tickets now: moonshot.techcabal.com

Leave a Reply